News

News

Mutuals are leading the charge in Open Banking

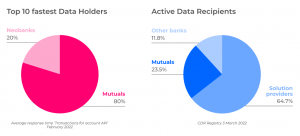

8 out of the 10 fastest Data Holders are customer owned banks

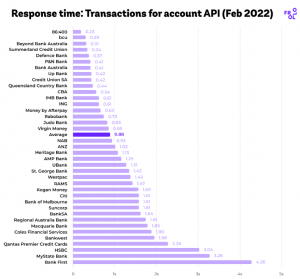

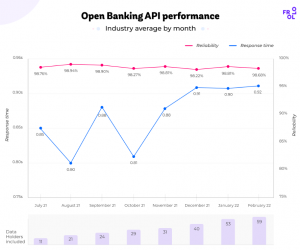

In Feb Frollow published their report on Open Banking API performance, comparing the speed and reliability of Data Holder APIs. The report shows that when providing transactional data, 8 out of the 10 fastest Data Holder brands are mutuals.

Though, the fastest Data Holder is not a mutual: Neobank 86:400 was fastest in February, just as they were the previous 5 months.

Mutuals aren’t just leading the way as Data Holders, some of them are establishing themselves as first movers in the use of Open Banking data too.

In February three customer owned banks became ‘Active’ on the CDR Registry as Data Recipients. P&N Bank, bcu and Beyond Bank all activated their connections using the Frollo Open Banking platform, as one of the final steps before launching their Open Banking powered financial wellbeing apps.

Tonina Iannicelli (Senior Manager, Digital, Beyond Bank) knows how critical it is to leverage technology for the benefit of their customers. “Open Banking provides us the opportunity to work for and with our customers by doing the heavy lifting on behalf of our customers, collecting their financial data from various institutions to help manage their finances – all in one place.

This is just the start, and we are excited to see how else we can work with our customers to get them decisions quicker, offer services that they value, and continue to nurture our relationship with them”.

P&N Group General Manager Technology Transformation, Erik Fenna, said unlike the listed banks, customer-owned banks such as the Group’s retail brands P&N Bank and bcu have a laser focus on customers rather than third-party shareholders, meaning the customer is at the heart of everything they do.

“We are focused on making banking easier for our customers by putting more control of their overall financial wellbeing and day to day banking in their hands through Open Banking,” Mr Fenna said.

“By offering customer-centric technology that solves key financial pain points, such as money management and the home loan application process, not only will we make it easy to bank with us, importantly we will also make it easy for our customers to get ahead.”

Simon Docherty (Chief Customer Officer, Frollo) isn’t surprised to see mutuals leading the way. He explains: “Open Banking offers the biggest opportunity for customer centric businesses, as it can unlock better customer experiences, as well as more personalised products and services.

Their focus on delivering value for customers has made Open Banking the perfect tool for mutuals to deliver on their promise, by providing financial wellbeing tools, improved access to credit and better deals on their finances.

We’re excited to help those early adopters in the mutual bank sector use Open Banking to deliver better customer outcomes.”

Source: Frollo March, 2022.

2020 Pandemic: How might it change the ways we pay?

2020 Pandemic: How might it change the ways we pay?

Although the total number of payments in the Australian market is currently suffering a severe decline, as economic activity is strongly curtailed, what might happen to the ways consumers pay after the 2020 pandemic? Guest writers, David Oierholm and Lance Blockley of The Initiatives Group, offer their view.

The COVID-19 2020 Pandemic is having an unprecedented impact on how we live and work. We are planning for the worst and hoping for something better. No matter how long it takes for the crisis to pass, 2020 will be a year that is not forgotten quickly.

It will undoubtedly be a period of change, some of which will alter the way we do things forever.

We are likely to wash our hands more frequently, and we will be much better at conducting remote meetings using platforms such as Zoom, Webex, Skype for Business, GoToMeetings, etc. Telemedicine will likely become more prevalent, as will the ability and propensity to work from home effectively.

We will be super-sensitised to microbes, and, given the economic impacts being experienced, we may be more concerned about the sustainability of the companies we buy things from, together perhaps with more conservative views regarding our ongoing employment and income. Indeed, the cross-border supply chains that have been constructed over the last 15+ years of globalisation have been shown to be a potential weakness (e.g. a key global production site of surgical masks being in Wuhan), so perhaps domestic manufacturing will get a boost everywhere and cross-border commercial transactions decline.

Although the total number of payments in the Australian market is currently suffering a severe decline, as economic activity is strongly curtailed, what might happen to the ways consumers pay? Not necessarily in the short term – although many merchants are now refusing to take cash, travel card issuance & usage has crashed, and cross-border payments (a key revenue source for the international schemes) are drying up. Rather, we are looking at the potential longer term residual impacts.

In The Initiatives Group white paper “The Changing Face of Consumer payments in Australia”, we identified that the way we pay takes a long time to change. It is all about trends, and long ones at that. The following graph was used to show how the ways we pay have changed over the past 15 years. The trends are clear – cash and cheques are on the decline, and fast becoming in the minority of transactions. Electronic payments continue to increase. Cards are now more than 60% of transactions, with the growth in debit cards far outstripping credit cards. It is now quite normal to pay for a morning coffee (currently only available as “take away”) using a card – not so long ago a $3.50 purchase would have been made with cash.

The trends are clear – cash and cheques are on the decline, and fast becoming in the minority of transactions. Electronic payments continue to increase. Cards are now more than 60% of transactions, with the growth in debit cards far outstripping credit cards. It is now quite normal to pay for a morning coffee (currently only available as “take away”) using a card – not so long ago a $3.50 purchase would have been made with cash.

What might happen to cash?

“Fed Plans Release of Clean Cash As Virus Spreads” (pymnts.com, March 22, 2020)

The decline in the use of cash will accelerate, along with an associated decline in ATM usage (noting that for every ATM withdrawal that does not happen, an additional 10-15 electronic transactions will be generated, mainly on debit cards).

Cash carries bacteria 1 (no prior studies seem to have focused on viruses!). Both cash and bacteria travel fast. Even though it has been found that polymer notes, like those used in Australia, carry less bacteria than (absorptive) paper notes such as those in the USA and China, consumers and merchants alike will be less keen on handling cash, and more keen on using electronic payments. Indeed, the UK has just lifted the contactless limit from GBP30 to GBP45 to help further reduce the use of cash. More locally in Australia, one of your authors has found that cash is no longer accepted at the local Coles Supermarket, Harris Farm Markets and the golf club (which is closed for now anyway).

Cash carries bacteria 1 (no prior studies seem to have focused on viruses!). Both cash and bacteria travel fast. Even though it has been found that polymer notes, like those used in Australia, carry less bacteria than (absorptive) paper notes such as those in the USA and China, consumers and merchants alike will be less keen on handling cash, and more keen on using electronic payments. Indeed, the UK has just lifted the contactless limit from GBP30 to GBP45 to help further reduce the use of cash. More locally in Australia, one of your authors has found that cash is no longer accepted at the local Coles Supermarket, Harris Farm Markets and the golf club (which is closed for now anyway).

So, are plastic cards the answer?

Australians are the world leaders in the use of contactless open-loop payments, with well in excess of 90% of card present transactions being contactless. This means that, for transactions under $100, we don’t need to touch a terminal that somebody else has used or handed us. We also don’t have to hand our card over to a stranger. That’s good, right?

Well, maybe not… unfortunately there are studies, albeit in the USA, where contactless payments are still in their infancy, that have shown that cards “can be grimier than cold hard cash”.2

However, it still feels safer to use a card that only you have held than notes and coins that have gone through multiple hands, so plastic cards will quickly pick up transactions from cash.

How about other transactions that use the card rails?

Mobile Wallets

Despite the high ownership of smartphones and Australians’ love of contactless payments, until recently, the take up of mobile wallets such as Apple Pay, Google Pay and Samsung Pay (the “Pays”) has been slow. It may depend on your industry and your demographic, but The Initiatives Group has heard conflicting reports. Claims of 25% of POS transactions being handled via the Pays have been offset by merchant claims of far far lower percentages, hence we would suggest that the average across all contactless payments is still under 10%.

Regardless, the use is set to accelerate. Your phone may or may not be a great carrier of bacteria, but it is something you will touch anyway, so what’s the difference if you now use it for payments and avoid fiddling around with your wallet for a card.

Wearables

Whilst wearables are only another form factor for using the Pays, their use is likely to increase as an even more “contactless contactless” form of payment. Notwithstanding we believe that wearables, perhaps other than smart watches, will remain relatively niche.

In-app payments

In-app payments are likely to be a big winner from the COVID-19 crisis. Seamless payments will be the most contactless of contactless payments. Whilst in the short-term popular use cases such as Uber transport will take a significant hit, there will be many new use cases that become available earlier or even more popular – think of ordering home delivery (from supermarkets, for prepared food e.g. Menulog, Ubereats) and petrol stations (where something like the Caltex app avoids the need to enter the shopfront). We will be more ready to form new “safe” habits, and, if used frequently enough, these use cases will be habit forming, just as the adoption of contactless card payments was slow until Woolworths and Coles offered them (back in 2012).

We found the new 13cabs “No Touch Parcel Deliveries” of interest. Whilst no-touch may not be as big a deal from 2021, here is another reason to get into the habit of using in-app payments for taxi services. In the future will we see the groceries delivered paid within the 13cabs app, or the taxi delivery paid for within the Coles or Woolworths app?

Peer to peer payments

As handling cash becomes less popular, might we now see electronic peer to peer payments use accelerate. Perhaps this will provide stimulus to the use of PayID, Beem It and card-tocard systems. Although current social distancing and work-fromhome orders may well diminish the need to pay our friends and relations in the near term.

eCommerce card not present

In the short-term, eCommerce spend on travel and discretionary items has tanked, however online ordering of grocery goods and fresh foods is up globally. Discretionary spend, such as fashion, will recover once people are again allowed to physically interact. Grocery and fresh food ordering online will be a new habit – whether for home, work or locker delivery, or click and collect. Although it may not maintain at COVID-19 levels, this will likely fuel more rapid long term growth in eCommerce retail spend.

Monthly payments

The economic impact of potential (or actual) unemployment, of recession and of media noise about depression, will all make consumers more wary of both the sustainability of companies that they deal with and their own ability to pay in annual large lump sums. We predict this will lead to a preference for annual payments to be made monthly (already a trend before the crisis), and not necessarily by auto direct debit (as consumers may wish to retain control). In addition, this preference may lead to consumers demanding that they are not penalised with any surcharge for paying monthly.

Noting that, just as the decline in ATM use accelerates the volume of electronic payments, so too does monthly payment . . . 12 transactions rather than one.

New products

Adversity is often the mother of invention, so it is likely that we will see a range of new electronic payment products, use cases and services being created.

Opportunities only for the card rails?

An emphatic “No”. As noted above, online real-time payments over the NPP may be accelerated – whether by Osko, other overlay services or by ‘pay anyone’ (previously via direct entry) payments growing faster. The increased volumes allowing the NPP to become less expensive per transaction.

Perhaps a trend towards mobile phone payments will improve the use case for NPP payments on your phone at POS, enabled by QR codes? Notwithstanding, we do expect that there will be even more new overlay service activity that takes advantage of the NPP.

Conclusion – How might Covid 2020 Pandemic Change the Way We Pay?

The current COVID-19 crisis will see payment volumes drop sharply as economic activity stalls. Within the remaining payment activity, the mix of payments will change:

- The reduction in cash and ATM usage that has been occurring over many years will accelerate into a steep decline

- The cross-border usage of payment cards will drop to low levels

- Use of contactless card and mobile payments will rise

- Use of remote services/ordering, and with them the associated remote payments (eCommerce, in-app, other online), will increase

- A move to monthly payments.

Depending upon the length of the crisis, many of these changes will become habitual and are likely to outlast the short term impact of the virus – such that the retail payments mix in the Australian economy will be altered forevermore.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the view of Indue. The Initiatives Group has advised participants in the payments market since the 1990’s – including issuers, acquirers, third-party processors, technology providers and associations. The Initiatives Group has a strong relationship with Indue, and can help participants in the payments sector generate more value from their markets and customers. To find out how, please get in touch.

Sources:

1 A Oxford University study in 2014 found that the average European banknote contained 26,000 bacteria which could be potentially harmful to a person’s health; and market research has found the majority of European consumers rank physical money as being more unhygienic than the hand rails on public transport

2 https://www.fastcompany.com/90480199/how-companies-can-support-their-employee-caregivers-duringthecovid-19-outbreak

Open Banking Delay: ACCC Update (March)

Open Banking Delay Update: Open Banking in Flux

In late December 2019, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) confirmed further delays to the scheduled launch of the Open Banking Regime.

Shifting Timelines of the Open Banking Regime and CDR

The first shift of the timeline was announced in January 2019 when Treasury released an updated timeline for the rollout of the Consumer Data Right (CDR) regime. The Open Banking delay was largely due to the need to continue testing the robustness of the new infrastructure, which saw the July 2019 original launch date evolve into the commencement of a beta testing phase for only the major banks.

The updated timeline had February 2020 set as the new targeted public launch date, where consumers would be able to instruct the major banks to share their credit card, debit card and deposit account data with accredited third parties.

The subsequent delay announced late last year shifted the February 2020 launch date to July 2020, a full 12-months after it was originally supposed to roll out.

Vigorous Security Mechanisms for Open Banking

One of the key objectives of the Open Banking reform is to foster fair and healthy competition within the finance industry. In order to achieve this, there needs to be the exchange of highly sensitive data, which requires vigorous security mechanisms to be in place and relies heavily on new privacy considerations. The ACCC confirmed the additional lead time will be used to ensure the comprehensive testing of a system that the Australian finance industry will have to adopt in earnest in the coming years.

“The CDR is a complex but fundamental competition and consumer reform and we are committed to delivering it only after we are confident the system is resilient, user-friendly and properly tested,” ACCC commissioner Sarah Court said.

“Robust privacy protection and information security are core features of the CDR and establishing appropriate regulatory settings and IT infrastructure cannot be rushed.”

Under the new timeframe, major banks will have to share data on credit and debit cards, deposit accounts and transaction accounts from July 1, 2020. From November 2020, the major banks must be able share information relating to mortgage and personal loan accounts.

For ADIs outside the Big Four banks, the delayed implementation timeline will be:

- 1 July 2020 – product data for deposit accounts, debit and credit card accounts to be shared

- 1 February 2021 – product data for mortgages to be shared

- 1 July 2021 – consumer data on each of these product types to be shared

Open Banking Delay & Accreditation Debate

The postponement of the launch may have also been indirectly affected by ongoing pressures amongst the finance community, namely the FinTechs and consumer groups. In a submission to a Senate inquiry into fintech policy, FinTech Australia described the accreditation process for open banking as one of its top concerns.

FinTech Australia is a member driven organisation that is building an ecosystem for Australian fintechs to advance the global economy. The organisation represents more than 300 start-ups in the financial sector.

“Requiring a company to become accredited, expending significant time and upfront costs, simply to undertake initial tests is cumbersome and economically unviable,” says the submission. FinTech Australia estimates it will likely cost upwards of $100,000 for a fintech to become an accredited data recipient, increasing the barrier of entry to the markets that would be affected by the new regime.

From a consumer perspective, the accreditation process should be as comprehensive and vigorous as possible given the nature of the data being shared. Consumer groups, in response to the same Senate inquiry, are supportive of the accreditation criteria and CDR rules. Fintechs should not be exempt from the full accreditation process and the CDC rules should evolve if loopholes surface. The Consumer Action Law Centre, who is a non-for-profit consumer advocacy organisation, stated in its joint submission with The Financial Rights Legal Centre that the industry will need “well resourced regulators to provide adequate oversight and amend and improve the standards and recommend changes to the governing legislation, when and where FinTech arbitrage leads to demonstrably poor consumer outcomes”.[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text el_class=”ind-textBox”]

References

Financial Technology and Regulatory Technology Inquiry Submissions

Insight: The changing face of consumer payments in Australia

Insight: The changing face of consumer payments in Australia

Our guest writer, David Oierholm, Director of The Initiatives Group, sheds light on the changes and trends of consumer payments in Australia.

The ways in which consumer payments in Australia are made is often likened to a train system comprised of the “rails” that carry the carriages (the payment systems), and the “carriages” that carry the passengers (the individual payments).

The media will have us believe that the payments landscape in Australia is constantly and rapidly changing. To an extent this is correct – but this is all about new “carriages” rather than “rails”.

Furthermore, simply because there are new ways to pay on offer, it does not mean that we all immediately change the way we pay. For example, it took well over 5 years for both BPAY and (much later) contactless card payments to become mainstream.

In Australia, there has only been one new set of rails introduced in the past 25 years (The New Payments Platform (NPP), 2018)

The Way We Pay

It is about trends, and long-term ones at that. The following graph shows how the ways we pay (our use of the rails) have changed over the past 16 years, exhibiting slow movements and not, as many media commentators would suggest, overnight leaps.

The trends are clear – cash (as proxied by ATM withdrawals) and cheque usage are on the decline, and fast becoming the minority of transactions. Electronic payments continue to increase. Cards now account for more than 50% of all payment transactions, with the growth in debit card activity far outstripping credit card since 2007. It is now quite normal to pay for a morning coffee using a card – not so long ago a $3.50 purchase would have been made with cash.

Will cash and cheques ever completely disappear? It is more likely that cheques will disappear, but only when the industry and/or regulator set a termination date – otherwise someone, somewhere will keep using them. However, the ability to access and use cash is considered critical for members of society who may be unbanked, and for remote residents where electronic payments may either be unavailable or inconsistent. Even in those economies closest to being cashless, such as Sweden, there are government requirements for the economy not to become cashless – at least not until no one is left behind or disenfranchised.

In 2019, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors passed a law requiring that all bricks and mortar retail businesses must accept cash – this even includes the Amazon Go stores (more about them later). This move is to make sure that the city’s poorest residents are not shut out of access to basic goods and services. Whereas “cash not accepted” signs are common in shops in Sweden.

The Rails

The rails for electronic payments in Australia include the card rails (Visa, Mastercard, Amex, eftpos), the rails for direct entry and direct debit payments known as BECS (Bulk Electronic Payment System), the real-time payments rails operated by New Payment Platform Australia (NPP) and the international bank to bank transfer rails (SWIFT). The only one of these sets of rails that has been introduced within the last 25 years is the NPP, launched last year.

(Source: The Initiatives Group)

The Carriages

What runs on the rails is where the new action has been, as a plethora of “veneers” have been placed on top of the payment rails, giving the perception that the movement of money has changed. What has changed, and greatly, is the consumer interface, which has become more convenient, simple to use, frictionless and seamless. But, as noted earlier, just because a new way to pay is being offered there is no guarantee that it will be used.

Mobile Wallets (Mobile Payments)

Mobile wallets such as Apple Pay, Google Pay and Samsung Pay, otherwise known as “The Pays”, have arguably received more media headlines than any other payments related topic over the past few years. Despite this, it is estimated that they represent fewer than 5% of card present transactions, albeit that there now seems to be some acceleration in the adoption rate.

Requiring a credit or debit card to fund a transaction, The Pays operate on the Visa, Mastercard, American Express and, to a lesser extent, the eftpos rails. They have been offered in Australia since 2015 when Apple Pay was launched with Amex.

Even though some would describe it as simply a new “form factor” – a contactless payment (now over 90% of card present transactions) using a phone rather than a plastic card – the rollout through the payments industry has been slow. A popular hypothesis is that using your phone currently offers little benefit over using a plastic card – that is, there is no value added.

In addition, there has been significant reticence amongst the major banks to fund the fees payable to Apple Pay, which also comes with the limitation of no other application being able to access the NFC interface on the iPhone. However, as of today the only major Australian bank that does not offer Apple Pay (considered the vanguard of The Pays) is Westpac, so it is felt that the current low usage rates will increase to more significant levels over the next few years, assisted by use on mass transit.

A different type of mobile wallet where you can “pre-fund” your account prior to purchase (or link to a “top up” source of funds) is particularly popular in China, and increasingly so throughout Asia. AliPay and WeChat Pay both from China are prime examples.

When making purchases, these systems run on their own sets of rails with the transaction driven by a QR code interface (overcoming Apple’s NFC quarantine). This has permitted significant growth in electronic payment acceptance due to the simple and low cost set up for the payee. However, to fund the account, money is transferred from the user’s card or bank account.

This means the funding uses existing payment rails. To date the use of QR codes in payments in Australia has primarily been limited to visiting Chinese tourists. Australians are already well served by NFC contactless payments, so, whilst there may be more value-adding capability within a QR code, there is little incentive for consumers to change.

Another popular wallet, although not so much in mobile format (at least not in Australia), is PayPal. Created as a payment wallet to make secure online transactions, the PayPal wallet can be instantly funded by a credit or debit account, or pre-funded. An interesting contrast is that in the US keeping funds in a PayPal wallet is popular, whereas in Australia it is not.

In-app Payments or “payments in the background”

Popularised by the success of the Uber rideshare app and the “just get out of the car at your destination and walk away” payment experience, in-app payments are the topic of a separate whitepaper published by The Initiatives Group.

Sometimes criticised for making it too easy for consumers to overspend as they do not have a “transaction moment” to reconsider their purchase, in-app payments are growing even faster than e-commerce. Prime examples include Uber – familiar to most of us; Grab, which dominates carshare in South East Asia, and which is now promoting its payment service in its own right as “GrabPay”; and the Hey You (Beat the Q) café pre-order and payment aggregator app.

In the USA, Starbucks is prolific enough to have its own pre-order and payment app, which accounts for a significant proportion of their sales and is integrated with the Starbucks Loyalty program. Further loyalty integrations are underway. For example, in the USA you can use American Express Membership Rewards points to pay for your Uber ride. Amazon is taking the in-app, seamless shopping and payment experience to the nth degree, (possibly out of the budgetary capabilities of most retailers) with its Amazon Go “no lines, no checkout” concept stores, it is extreme but an insight into what is already possible!

In Australia, Woolworths is currently trialling “Scan & Go” with selected Woolworths Rewards loyalty members in Sydney – it is a variation on Amazon Go, where shoppers scan items when they take them from the shelf and then just tap off when leaving the store. This is important, as Woolworths and Coles are able to move the market: it was really not until they adopted the NFC technology that contactless payments became commonplace in Australia.

The Form Factor

Many innovations on the existing payment rails are actually changes in the form factor. As noted earlier, mobile payments are, for the most part today, simply the ability to use your phone to make a contactless card payment, rather than use the physical card itself.

Other new form factors include smart watches, including the Apple watch, Samsung Gear watches, as well as Garmin and Fitbit with Garmin Pay and Fitbit Pay respectively. Similarly, there are wrist bands and tabs attached to watch bands, even sunglasses and jewellery, such as the Bankwest Halo Payment rings. Current opinion is that these “wearables” will become popular, but amongst niche groups rather than the general population – for example waterproof bands and rings for swimmers, surfers, runners and cyclists.

BPAY and Pay Anyone

BPAY and Pay Anyone (Direct Credit on internet banking or a banking app) are payment methods that use the BECS Direct Entry system. Both allow for bank account to bank account transfers five days a week (excluding Public Holidays), with banks transferring funds 5 times per day (but not necessarily posting them to accounts that frequently).

Reliable, secure and low cost, however it is possible that a transfer can take some time to occur or appear in the receiving account – if the transfer is made late on Friday afternoon and is to a bank that is not posting intra-day settlements it may not be until the following Tuesday that the funds appear in the recipient’s account.

Whilst BPAY volume continues to grow, BPAY now somewhat competes with itself as the provider of the first “overlay” service “Osko” for the NPP, which allows real time payments between consumers and businesses via BSB and account number or with a registered PayID (mobile number, email address or ABN) linked to their bank account. Further, a number of Financial Institutions have and are moving their Pay Anyone / Direct Credit transactions onto the NPP rails, instead of using BECS.

P2P (peer-to peer) Payments

Particularly popular in geographies as diverse as the USA and China (perhaps due to the antiquated and previously limited payment systems available), P2P payments allow instant payments between consumers – splitting the bar tab, paying your share of the rent, getting money to the kids quickly, etc.

Venmo (now owned by PayPal) in the USA and WeChat Pay in China are prime examples. Both allow instant payments between other Venmo or WeChat Pay users from a pre-funded wallet. Perhaps they could be considered alternative rails, however, funding still comes from the existing rails transfer methods as these are linked to accounts.

In Australia, BeemIt allows P2P payments between BeemIt users, requiring only a Visa or Mastercard debit card for registration. Interestingly, BeemIt accesses bank accounts by using Visa and Mastercard for the authorisation messaging, then uses the eftpos rails to achieve the instant funds transfer.

As with many new ways to pay, BeemIt has not (yet) become popular in Australia as it has yet to gain sufficient penetration or ubiquity, and perhaps does not solve a significant problem that Australian consumers have (given the various other ways that they have to pay).

Real-time Payments

The establishment of real time payments platforms, moving and posting money between accounts 24×7, such as Australia’s NPP, is a major global trend. The UK has had “Faster Payments” and Singapore “FAST” for some time. More recently, Malaysia “DuitNow” and TCH (“The Clearing House”) in the USA have introduced real time payment platforms.

The NPP was launched in February 2018, the first new payment rails in Australia for 25 years (the prior launch was BECS in 1993). The NPP is an initiative that was primarily driven by the Reserve Bank of Australia, following its review of innovation in payments, and is co-owned by 13 banking organisations. It allows for real time payments between bank accounts.

To date, it has been held back by a somewhat uncoordinated introduction through the banking system. Whilst over 2 million PayID’s have been registered, use of the Osko payment “overlay service” has been relatively limited. This is likely to change once all banks deliver the range of features available, more entities register PayID, and business applications such as “Request to Pay” and a central consent management platform are delivered (effectively allowing Direct Debit transactions to be introduced by the NPP).

To date, it has been held back by a somewhat uncoordinated introduction through the banking system. Whilst over 2 million PayID’s have been registered, use of the Osko payment “overlay service” has been relatively limited. This is likely to change once all banks deliver the range of features available, more entities register PayID, and business applications such as “Request to Pay” and a central consent management platform are delivered (effectively allowing Direct Debit transactions to be introduced by the NPP).

Even Sweden’s “Swish” success story has taken almost 7 years since its establishment in 2012 to reach a total of 1 billion transactions through the system.

Use cases range from instant P2P payments, to real time payment of employee wages, superannuation, even to the ability to safely buy/sell a used car privately on the weekend without the need for cash transfers or bank cheques.

(Image Source: Osko.com.au)

Real-time / Faster Cross Border Payments

Cross border account to account payments have primarily been the domain of Swift and its 165 member banks. Even if the origin or destination banks are not members, the 165 banks can act as “correspondent” banks to route funds into the recipient country and currency, then onto the recipient bank. It is reliable, but can be slow, opaque and relatively expensive. The Swift rails also enable currency transfer services such as Western Union.

Faced with the emerging faster cross border payment challengers, such as crypto currencies, Ripple, Visa B2B Connect, and Visa and Mastercard acquiring FX transfer platforms, Swift has been developing faster, lower cost transfer products to enhance its existing rails. Swift GPI (Global Payment Innovation) is now conducting faster cross border payment trials, and is poised for rollout network wide.

Swift, which also provides the distributed switching platform for Australia’s NPP, is also testing its involvement in integrating the different real-time payments platforms between countries.

Thought too slow and expensive (today) for domestic payments, cryptocurrencies and distributed ledger technology is of interest for the future of cross border payments, although there is a long way to go. For example, Bitcoin transactions can occur at between 10-20 transactions a second (versus Visa at up to 56,000 per second), and crypto currencies are infamous for the volatility of their value in fiat.

However, the announcement in June 2019 of the Libra Foundation, with its bundled currency backed blockchain based “stablecoin”, and the Facebook developed Calibra payment wallet (planned to be the first wallet for Libra transactions) has generated significant excitement and debate. Whether or not is succeeds (or even permitted to launch by regulators), it raises the possibilities of western “bigtech” finally entering the payments (and broader financial services) category, and the possibility of a truly global currency that transcends fiat currencies and national borders – at the same time, reaching one of the world’s broadest social network audiences.

Will Libra run on new rails? Within the Calibra wallet this is likely, but Libra ultimately still needs to be funded from some other electronic source such as a bank account or card (even if unbanked users pass cash across the counter at “agent” locations). Indeed, it has been suggested that, to reach merchants for POS transactions, it may use the Visa and Mastercard rails.

There will be many legislative hurdles to overcome, and, in developed countries such as Australia with highly developed payments systems, there remains the question of what real problems are Libra and Calibra really trying to solve (maybe remittances?).

Use cases range from instant P2P payments, to real time payment of employee wages, superannuation, even to the ability to safely buy/sell a used car privately on the weekend without the need for cash transfers or bank cheques.

Buy Now, Pay Later (BNPL)

With millions of customers in Australia, the USA and soon in the UK, “I’ll AfterPay it” is becoming a familiar expression. AfterPay, Zip Money, Humm and SplitIt have become particularly popular amongst millennials – Afterpay claims 69% of its users are 18-35 years old.

New way to pay, on new rails? No. Latitude and Flexigroup have been offering interest free payment plans for decades, and products such as Afterpay rely on debit and credit cards to make initial payments and subsequent repayments.

However, Afterpay and its cohort have tapped a rich vein of new business – millennials who are not migrating to credit cards, with a short-term low value instalment payment product, tuned initially for online purchases and delivered digitally. Merchants with a sufficient margin structure to absorb the 4-6% fee, see the additional sales as a boon in what is currently a tough retail environment. Add to this a group of BNPL businesses, those delivering similar products to small businesses, such as ProspaPay.

Conclusion – Consumer Payments in Australia

The adoption of electronic payments by consumers and businesses in Australia continues apace, pushing cheque and cash transactions (although not the amount of cash on issue) into a relatively steep decline. Consumer payments are dominated in volume by card-based transactions, but the format of these is starting to become “buried” under layers of “veneer” interfaces, many of which rely on card-on-file for their funding source.

To the consumer, these veneers look like “new ways to pay” and certainly deliver the more convenient and seamless experience that people seem to be seeking. But underneath, the funds are moving between the payer and payee accounts as they have always done.

The new rails provided by the NPP will not generate any new transactions in the market, but will take volume from existing systems. For the sake of efficiency and the economy, one hopes that the NPP will accelerate the decline in cash usage and lead to the termination of cheques. But it will also take volume from Direct Entry and card payments. Just as Swish has entered ecommerce and the point of sale market in Sweden, once the cost of NPP transactions reduces (as it should with volume growth) then one would expect it will also appear in the online and POS environments.

The increasing use of electronic payments in Australia should see the overall cost of payments as a percentage of GDP decline and the tax take through GST and income tax rise – both of which are beneficial for the country.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the view of Indue. The Initiatives Group has advised participants in the payments market since the 1990’s – including issuers, acquirers, third-party processors, technology providers and associations. The Initiatives Group has a strong relationship with Indue, and can help participants in the payments sector generate more value from their markets and customers. To find out how, please get in touch.

Open Banking Privacy Rules Released

Open Banking Privacy Rules Released

Draft privacy safeguards released for consultation.

An extensive set of privacy rules that will accompany the introduction of the Consumer Data Right (CDR), including Open Banking, will be legally binding statutory provisions.

The Office of the Australian Information Commissioner has released draft privacy safeguards for consultation. They cover consent rules, disclosure and reporting obligations, limits on data collection, obligations to destroy certain data, and OAIC enforcement powers.Some of the privacy safeguards will apply in parallel with the Australian Privacy Principles, while others will override APPs.

The Consumer Data Right is designed to give people greater choice over how their personal data is used and disclosed. It allows consumers to access particular data and transfer it to an accredited person.

The Information Commissioner will have power to investigate possible breaches of the privacy safeguards and use a range of enforcement powers, including penalties.

The OAIC says the CDR system is built on consent, and an accredited person may only collect and use CDR data with the consent of the consumer.

A consumer can withdraw consent at any time.

An accredited person must not collect more data than is reasonably needed in order to provide the requested goods or services.

Each accredited person and each data holder must provide a “consumer dashboard” for CDR consumers, which is an online service consumers can use to manage data requests, authorisations and associated consents for the accredited person to collect and use CDR data.

CDR entities must have a policy describing how they manage CDR data. The policy must be available free of charge. They must handle CDR data in a clear and transparent way.

Accredited data recipients must provide consumers with the option if dealing anonymously or “pseudonymously” with the entity. Consumers must have the option of not identifying themselves.

In the banking sector, an accredited data recipient will not be able to deal with a consumer ion an anonymous basis because there may be obligations to verify identity prior to providing goods and services.

Accredited persons are prohibited from attempting to collect data under CDR unless it is in response to a “valid request” from the consumer. The CDR regime is driven by the consumer.

Accredited persons are required to destroy unsolicited data that the entity is not required to retain.

Accredited persons must notify the relevant consumer when they collect CDR data. This must be done through the consumer dashboard.

CDR data cannot be used for direct marketing.

Open Banking Update: Consumer Data Right Legislation (CDR)

Open Banking Update: CDR Legislation

The Federal Government recently passed the Consumer Data Right (CDR) legislation, which ushers in the new era of Open Banking for the financial sector.

On 1 August 2019, the Federal Government passed the Treasury Laws Amendment (Consumer Data Right) Bill 2019, which subsequently received Royal Assent on 12 August 2019. Open Banking is the first instalment of the Consumer Data Right legislation (CDR) in Australia, which gives individuals more control over their own data.

This legislation will allow individuals and businesses the right to obtain certain types of their data, which they have already shared with their financial institution, as well as provide authorised third parties access to this data.

Open Banking Rules & Guidelines

The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) has since published the final version of the Consumer Data Right (CDR) legislation governing elements that are central to the implementation of the CDR in the financial sector.

As the CDR regime will allow consumers to request data holders to provide their data to accredited entities, the ACCC have now also released draft guidelines on the CDR accreditation process and on the insurance and information security requirements of accreditation. The intent of the guidelines is to provide information to assist applicants with lodging an application for accreditation as well as guidance on how applicants are to meet the obligations to protect data from misuse and unauthorised access.

Timeline

The current CDR regime rollout timeline is as follows:

| Date | Requirement |

| July 1, 2019 | Big 4 Banks to provide generic product data for deposit accounts and credit cards via API |

| Feb 1, 2020 | Big 4 Banks to provide customer specific data for deposit accounts and credit cards, and generic data for mortgages and home loans, mortgage offset accounts and personal loans, via API |

| July 1, 2020 | All other ADIs to provide generic data for deposit accounts and credit cards via API |

| July 1, 2020 | Big 4 Banks to provide customer specific data for mortgages and mortgage offset accounts, and generic data for all other loans, leases and specialist accounts (e.g. trust accounts, pensioner deeming accounts), via API |

| Feb 1, 2021 | All other ADIs to provide customer specific data for deposit accounts and credit cards via API, and generic data for home loans, mortgage offset accounts and personal loans via API |

| Feb 1, 2021 | Big 4 Banks to provide customer specific data for all other loans, leases and specialist accounts (e.g. trust accounts, pensioner deeming accounts) via API |

| July 1, 2021 | All other ADIs to provide generic data for all other loans, leases and specialist accounts (e.g. trust accounts, pensioner deeming accounts), and customer specific data for home loans, personal loans and mortgage offset accounts, via API |

| Feb 1, 2022 | All other ADIs to provide customer specific data for all other loans, leases and specialist accounts (e.g. trust accounts, pensioner deeming accounts) via API |

The ACCC has advised that the Big 4 Banks have already commenced providing generic product data (as required by 1 July 2019) on a pilot basis. The ACCC has also now selected ten entities to participate in the testing of the CDR ecosystem in the run up to the next milestone in February 2020. The selected participants offer a broad range of innovative services to consumers, including services to manage personal finances, facilitate book keeping and assess a consumer’s financial status.

Requirements for Indue ADI Clients

From 1 July 2020, all of Indue’s ADI clients will be required to meet the obligation advised above. The required APIs for data transfer will need to be developed in accordance to the Consumer Data Standards, which have been finalised by CSIRO’s Data61 as the appointed Data Standards Body for the CDR regime. Indue recommends that clients engage with their core banking platforms to understand what API solutions are available to support these new requirements.

Indue is currently looking into opportunities for hosting client sessions on Open Banking to assist in the understanding of requirements, impacts and implications of this new data regime for our clients.

References

Open Banking Delayed – Instilling Trust in the System

Open Banking Delayed – Instilling Trust in the System

In late December 2018, Treasurer Josh Frydenberg announced that the targeted open banking launch in Australia would be delayed by eight months.

The initial 1 July 2019 public launch date has now been revised, with open banking delayed to encompass only a ‘pilot program’ to test the system. I

nstead of the commencement of actual data sharing capabilities for consumers, the ACCC and Data61 will collaborate closely with the Big Four banks to test the security, performance and reliability of the system. Other banks, fintechs and consumers who have expressed interest in participating in the pilot test will also be invited to contribute.

Open Banking is the first instalment of the Consumer Data Right (CDR) legislation in Australia, which gives individuals more control over their own data. This legislation will allow individuals and businesses the right to obtain certain types of their data, which they have already shared with their financial institution, as well as provide authorised third parties access to this data.

The revised requirement timelines are as follows:

|

1 July 2019

|

|

1 February 2020

|

|

1 July 2020

|

|

1 February 2021

|

|

1 July 2021

|

The revised timeline follows the release of the Rules Outline for the Consumer Data Right by the ACCC late December 2018. The Consumer Data Right bill has not yet been introduced into parliament. Once the bill is formally passed, the rules will be formally implemented into practice.

Industry feedback on the open banking delay

Industry feedback on the delay has been varied. The FinTech sector will likely not be too impressed with the delay as Open Banking has been touted as an industry “game-changer” that will level the playing field and allow traditionally smaller players to be competitive on more fronts. However, most stakeholders including consumers will see the value in the delay if it ensures that the industry is implementing a robust, reliable and secure system given the content that is being shared.

Open Banking can only be successful if there is inherent trust in the system and this new test phase will likely strengthen that confidence.

How fintechs are responding to the Royal Commission

How fintechs are responding to the Royal Commission

The 76 recommendations of Hayne’s final report have been made public, but do Australia’s fintechs think it will change banking?

Article first published 5 February 2019, Finder.com.au. Author Elizabeth Barry

The final report of The Royal Commission into the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry has been handed down by Kenneth Hayne AC QC, and all firms in Australia’s financial industry, which includes fintechs, are taking it in.

The report made made 76 recommendations in total, including that borrowers should pay mortgage broker fees and that consumer protection laws should be extended to small business loans of under $5 million. The recommendations were focused on Australia’s financial regulators and financial institutions, but depending on the changes that are made, the recommendations would have an impact on the entire financial services industry.

CEO and founder of Australian neobank Xinja Eric Wilson said the reality is that we have “reached a new low”.

“But the report is a line in the sand and marks a real opportunity to shake up the industry and redesign it in the interests of customers,” said Wilson.

Wilson believes the rise of fintechs like Xinja and open banking, due to begin in Australia later this year, will offer a different model for consumers.

“Competition is the silver bullet. The emergence of neobanks like Xinja, which offer a different model, means that people poorly treated by their banks will be able to shop around. It will also become much easier to switch, with the rollout of open banking.”

The introduction in Australia later this year of open banking, which will hand consumers their data allowing them to aggregate information and shift banks or financial services providers more easily, will go a long way to easing the legwork around switching.

Brett King, advisor to the Xinja board and management and former banking adviser to the Obama White House said: “The Royal Commission identified a range of problems and inadequacies in the current system, addressing them requires more than just putting a new face on old banks.

“The emergence of challenger banks, like Xinja, enable us to design, from the ground up ethical, modern and inclusive financial services, without the baggage of the traditional players.”

“Fintech startups and investors with rent seeking, ethically questionable business models, based on selling private individual data, having high or hidden fees, exploiting customer ignorance or financial desperation, should be on notice and will face the risk of criminal charges. Change is coming and it is not just going to impact the big banks.

“Fintech needs to build around ethical, sustainable business models. In a sector devoid of trust, fintech startups can differentiate themselves and shine a new light of openness and transparency.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text el_class=”ind-textBox”]Founder and CEO of Roll-it-Super, Mark MacLeod, said the Royal Commission evidenced a financial services sector “riddled with conflicts of interest and greed” and that any fintechs with similar notions should take notice.

“Fintech startups and investors with rent seeking, ethically questionable business models, based on selling private individual data, having high or hidden fees, exploiting customer ignorance or financial desperation, should be on notice and will face the risk of criminal charges. Change is coming and it is not just going to impact the big banks.

“Fintech needs to build around ethical, sustainable business models. In a sector devoid of trust, fintech startups can differentiate themselves and shine a new light of openness and transparency.”

Source: www.finder.com.au Read full article here.

Open Banking: The Brave New World

Open Banking: The Brave New World

In August 2018, the Federal Government released the draft Consumer Data Right (CDR) legislation, which gives consumers more control over their own data.

This legislation will allow individuals and businesses the right to obtain certain types of their data, which they have already shared with their financial institution, as well as provide authorised third parties access to this data. The Australian government will apply this new legislation to the banking sector first with telecommunications and energy sectors to follow. The following is the approximate timeline for adoption of the new open banking framework:

| Date | Requirement |

| 1 July 2019 | Four major banks will be required to make credit and debit card data as well as deposit and transaction account data available under this new framework |

| 1 February 2020 | Four major banks will be required to make mortgage data available |

| 1 July 2020 |

Four major banks will be required to make all other data covered under the CDR available All other banks or Authorised Deposit-Taking Institutions (ADIs) will be required to make credit and debit card data as well as deposit and transaction account data available |

| 1 February 2021 | All other banks or ADIs will be required to make mortgage data available |

| 1 July 2021 | All other banks or ADIs will be required to make all other data covered under the CDR available |

API Economy

The Federal Government appointed CSIRO’s Data 61 group to advise and facilitate the creation of a set of technical standards that will underpin this consumer-driven data sharing. The access to the data will be made possible through the use of Application Programming Interfaces (APIs). All accredited parties will be required to build to these common standards in order to retrieve the authorised data. Data 61 recently released the first draft of these standards, which was open for industry feedback. The working draft standards are underpinned by four key principles: 1) the APIs are secure; 2) the APIs will use open standards; 3) the APIs will provide a good customer experience; and 4) the APIs will provide a good developer experience. As the foundation of the framework will be based on these common and fair objectives, it will certainly level the playing field for those willing to participate and reinforce a technical low barrier for entry.

Consumers in the Driver’s Seat

With the ability to control their own data and who can access their data, consumers will now be in a position of power. They can approach different financial institutions and be equipped with the knowledge that each institution can access relevant historical financial data (with the consumer’s permission) held on the consumer’s behalf. This consumer-authorised access will make the process of changing products and services across financial institutions much easier for the consumer. Prior to this new framework, a consumer would have to organise with the originating financial institution access to the relevant data and documentation and then proceed to engage other prospective financial institutions for available options with the relevant data at hand. Once this new regime is in force, it could be as simple as the consumer contacting multiple financial institutions, authorising access to the data and simply requesting their best offer. What was once cumbersome and prohibitive will now be a much more streamlined process.

With open banking, the industry will likely see the rise of the well-informed consumer. This type of consumer will recognise the benefits of having this data in making decisions on financial services or products that are right for them. They will question their current situation and will not simply maintain status quo due to indifference or idleness. This cohort can be split into two types – the negotiator or the sampler. The negotiators will leverage the fact that data can be made available to competitors and potentially drive their current financial institutions to offer better options. These customers still see the benefit of having most financial products with the one provider – economies of scale, convenience of a one-stop shop and potentially less fees. The samplers will not be concerned with having products and services across multiple financial institutions given they can shop around much more efficiently. They will be driven by the most attractive offer regardless of provider. Irrespective of type, the well-informed consumer will have more knowledge. Knowledge is power and the balance is about to be tipped towards the consumer.

Open Playing Field

With the ability for financial institutions or authorised third parties to access data more easily, open banking will stimulate unprecedented consumer-driven innovation. Banks will need to differentiate themselves from the competition by offering attractive incentives or new capabilities to enhance their existing product and services suite. However, financial institutions will not be the only entities that can access consumer data – any accredited parties will be privy to the information, which could include fintechs, start-ups, or the tech giants like Apple and Google.

With such a diverse set of bank and non-bank stakeholders, new areas of competition will be created and a new financial service ecosystem will be born. A small micro-lender may be authorised to review a customer’s credit card account history and discern the customer’s ability to pay off the loan based on account data. Equipped with this valuable information, the lender can tailor an appropriate loan with specific conditions for the customer. A prepaid card provider may access a customer’s account history held in another financial institution and offer a prepaid card with specific limits for certain spend types as a budgeting tool. Open banking will effectively remove the advantage that historically resides with the dataholder (in most cases – the financial institution).

Privacy & Fraud

One of the main concerns regarding open banking is the security and privacy of data. With an increased flow of data between parties, the challenge is to ensure that the transfer is secure and aligns with industry privacy standards. Under this framework, the consumer must provide their consent to who can access their data and for what purpose. In order to do so, they must have confidence in the system and how their data is stored, transferred and used. The Australian Competition & Consumer Commission (ACCC) has been tasked with developing rules and an accreditation scheme to govern the implementation of the consumer data right, approving technical standards, and taking enforcement action to ensure compliance by participants. Consumers and third parties need to trust the system if they are to use it in earnest and reap the benefits that open banking can provide the broader financial industry. Data privacy will be heavily scrutinised in the next few months.

Industry considerations will also have to be made on the impacts to financial crimes with the introduction of open banking. With the potential segregation of data to multiple third parties, individual organisations will no longer hold an all-encompassing view on a customer and as such not be able to detect anomalous patterns or behaviours as easily. The industry may also see a rise in fraudsters trying to impersonate accredited third parties to obtain confidential consumer account information. What is certain is the fact that financial crimes monitoring and data analytics will need to adapt to these changes in data source and data set to ensure that consumers continue to be protected from fraud exposure.

Preparing for the Storm

As the industry is targeting the first phase of open banking to be in force by the middle of next year, the industry must look to prepare for this new paradigm shift. Some suggested areas of focus:

- API – understanding existing API library and resources and what needs to occur to support the new industry standards

- Data analytics – explore options for extracting the most value out of current data or new types of data

- Strategic partnering – consider collaborations with other organisations that may be advantageous in the open banking world

- Banking platform – understand the implications of processing a larger data load, actioning data retrieval requests and presenting data to consumers

- Policy updates – look to commence updating internal policies relating to privacy, data storage, security and customer consent

Open Banking a Blueprint for a New Data Economy

Open Banking a Blueprint for a New Data Economy

Source: Australian Financial Review Feb 12 2018

Senior Treasury officials say the “open banking” report by King & Wood Mallesons partner Scott Farrell is one of the best policy documents they have ever seen produced by a professional in the private sector. It needed to be, given its implications.

Open banking will empower a customer to direct their bank to send their data to another provider. It promises to level the competitive playing field by reducing the costs of account switching and facilitating price discovery.

The banking sector is the first cab off the rank with customer data to be liberalised across the economy under a new Consumer Data Right announced in November. Telecommunications and energy will follow. Beyond that, data relating to health and education, and broader financial services such as insurance and superannuation, could also be put under the control of the customer.

A new data industry could be created as more people realise their data has a value and should be treated as an asset.

Farrell may work in rarefied air atop Governor Phillip Tower as a partner at King & Wood Mallesons, but his is a report centred on the person on the street. Under open banking, it will be customers in control of what data is shared and when.

Strong Stance

He is also willing to stand up to the power of the banks. In its submission to the review, the Australian Bankers’ Association called for the accreditation utility that will determine who can receive data to be run by the industry. Farrell rejected this, preferring the independent ACCC.

“Accreditation criteria should not create an unnecessary barrier to entry,” the report says.

The banks will also be distanced from controlling the technical standards for facilitating the data transfer. “Although financials institutions have largely welcomed the prospect of open banking, conflicts between their commercial considerations and the interest of consumers could easily arise,” Farrell writes.

Delivery will be via application programming interfaces (APIs). For technically minded readers, Farrell favours the OAuth2 framework for authorisation, providing minimal disruption to the user experience, with RESTful (representational state transfer) API architecture as the method of delivery.

The blueprint is Britain’s technical standard; it was designed by the British Open Data Institute, co-founded by world wide web inventor Tim Berners-Lee, and Fingleton Associates. Local standards will be developed by a data standards body.

Report Features

There are a few other striking features of Farrell’s 158-page report, which was released on Friday. The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission is a big winner: it will take the leading regulatory role to ensure the system works for consumers, with the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner overseeing privacy. The financial regulators will be interested onlookers.

Security will be paramount and customer trust will be enhanced through an accreditation regime and a liability framework.

There won’t be any centralised storage of the data, avoiding a “honeypot” that could tempt hackers, like those that penetrated Equifax and got access to the credit information of 143 million Americans.

“Fortunately, the principles used with money, communications and energy systems should show what could be needed for the sustainability of a stable, broader data ecosystem,” Farrell says.

In terms of timeframes, Morrison wants the regime up and running by July 1 next year. While API development work will be needed; the major banks are understood to be able to meet it.

Farrell also points to how open data will improve the quality of artificial intelligence engines. Perhaps the regime’s biggest impact will not come from what one bank can do with data from another bank, but what a company in another industry does with banking data.

A customer directing their bank to send data to their telco “could enable an entirely new field of products and services to be offered, enhancing choice and convenience”, Farrell predicts.

A risk for incumbents is they fail to grasp the opportunity to turn open data to their advantage, rendering them a mere utility providing the pipes, but not the customer experience.

Review Into Open Banking

Review into Open Banking

PRESS RELEASE: The Turnbull Government will act to improve customer outcomes and increase competition in the financial sector by implementing the recommendations in the final report of its independent Review into Open Banking.

Implementation will be phased in from July 2019, paving the way for the introduction of the Government’s Consumer Data Right in the banking sector.

Open Banking has the potential to transform the competitive landscape in financial services and the way in which Australians interact with the banking system. It will give banking customers greater access to the data their banks hold on them and the ability to direct that it be safely transferred to trusted and accredited service providers of their choice.

Customers will be able to use their new data rights to find better deals on their credit cards, mortgages and other banking products. Comparison services will be better able to assess the value and suitability of all available products, taking into account the individual circumstances and needs of the customer. This will help to break down barriers that see customers staying with their banks even when there are better deals elsewhere.

Open Banking will also allow entrepreneurs to develop new services and products tailored to customers’ needs, disrupting those existing business models within the banking sector that do not put customers first.

Importantly, the Government has committed to the blueprint proposed by the Review for ensuring strong privacy protections and information security for customers’ banking data. A key element of these protections is that only trusted and accredited recipients will be permitted to access data, only with customers’ express consent and only for the purposes the customer has expressly permitted.

The Government has set a challenging but realistic timeframe for bringing the benefits of the Open Banking reforms to consumers, with a July 2019 commencement.

Open Banking will be phased in with the aim that all major banks will make data available on credit and debit card, deposit and transaction accounts by 1 July 2019 and mortgages by 1 February 2020. Data on all products recommended by the Review will be available by 1 July 2020. All remaining banks will be required to implement Open Banking with a 12-month delay on timelines compared to the major banks. The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) will be empowered to adjust timeframes if necessary.

The ACCC will be responsible for promoting competition and customer-focussed outcomes within the system, while the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) will ensure that privacy protection is a fundamental feature of the system.

Data61, the data arm of the CSIRO, will be appointed to perform the role of a Data Standards Body, developing technical standards for the system in collaboration with industry, FinTechs, and consumer and privacy groups.

Open Banking will be implemented as part of the Consumer Data Right in Australia, a more general right to data established by the Turnbull Government currently being created across the economy following a recommendation by the Productivity Commission’s Data Availability and Use Inquiry. The Consumer Data Right will be established sector-by-sector, beginning in the banking, energy and telecommunications sectors.

Further information about how Australians can benefit from Open Banking and the Consumer Data Right can also be found in the downloadable handout.

For more information visit the Consumer Data Right page on the Treasury website.

Contacts: Andrew Carswell 0418 505 376, Kate Williams 0429 584 675, Sonia Gentile 0455 050 007

The Hon. Scott Morrison MP, Sydney

Click here to download the ACCC Press Release relating to Open Banking.